Alex Wen's Homepage

Should you run in the rain to stay dry?

When faced with a downpour, a natural instinct is to run, so we don’t get too wet - but does it really help? If it does, then should we run as fast as we can? Is there an optimal speed? And what if the rain falls at an angle? I thought I’d sit down and try to reason this out…

The Back of the Napkin

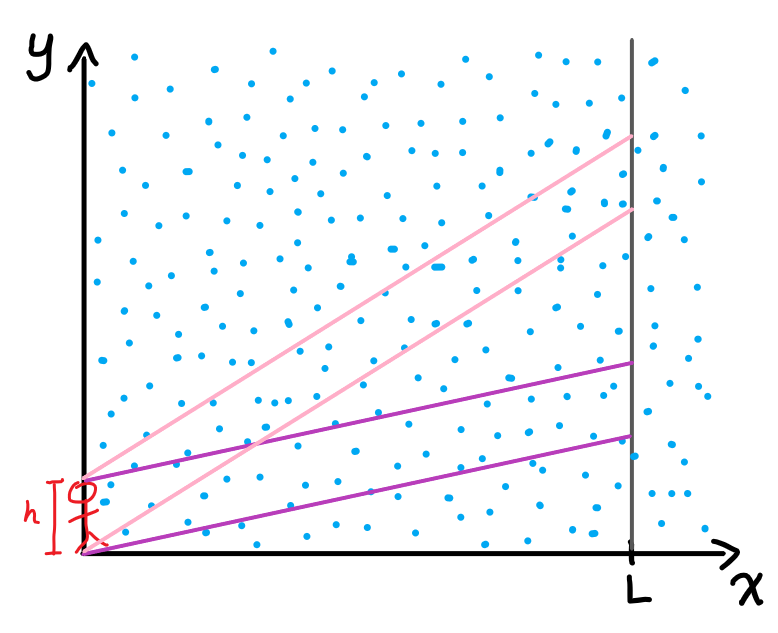

Imagine what the rain sees. From its perspective, it’s a stationary collection of water droplets while the world (and you!) rush up to meet it. If we make a plot from the point of view where the raindrops are stationary, with horizontal distance $x$ on the x-axis and vertical distance $y$ on the y-axis, then to cross the distance $L$, you have to move horizontally but also necessarily vertically up as well (you can think of $y$ being directly proportional to time, $t$):

As a result, you carve out a path in the raindrops that looks like a parallelogram. The faster you run, the less time you take, so you cover less distance vertically - the purple path is faster than the pink path.

The area of this parallelogram is significant, because it’s proportional to the number of raindrops you intersect on your journey, and therefore how wet you get. The funny thing about areas of parallelograms is that they only depend on the base length and the vertical height, not how slanted it is. The paths marked by pink and purple cover the exact same area - in this case, base ($h$) times length ($L$).

So, very roughly, we should expect the number of raindrops that hit us to be the same, no matter the speed.

Accounting for Thickness

However, that wasn’t a good solution, because people are usually thick. What I mean is, they have a width, not just a height, and that gives more exposure to the rain.

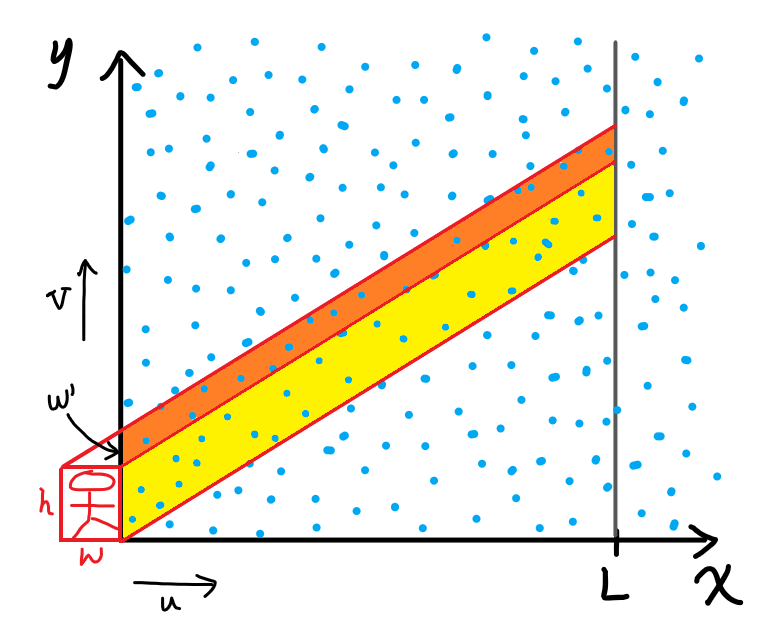

Let’s say that a person with width $w$ and height $h$ can be thought of as a neat rectangle that can be rained on, both on top and on the side. Again, let’s draw the same plot of $x$ and $y$, from the perspective of the rain. All the raindrops stay still, and you’re moving both across and up. The rain falls at a vertical speed $V$ and you move at a horizontal speed $u$.

The yellow parallelogram is the same as before when we didn’t consider thickness; to get its area, we simply take $h \times L$.

The orange parallelogram is the part that comes from thickness. To get its area, we need to find the quantity labelled $w’$.

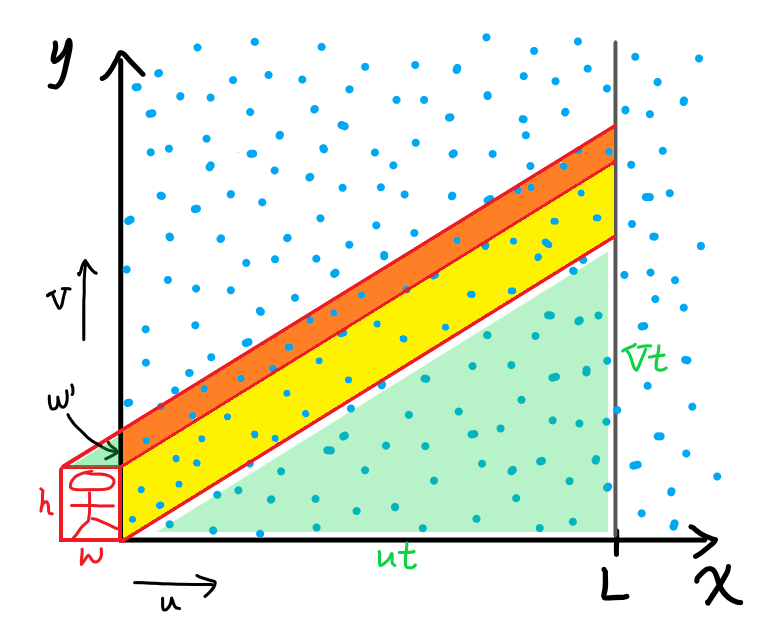

Let’s begin by noticing that the little triangle above the person is similar to the large triangle under the yellow parallelogram:

The two green triangles are just scaled up/down versions of each other; therefore, the ratio of their side lengths must be the same. For the large triangle, in the same time $t$ elapsed, it will move $Vt$ upwards and $ut$ across. So the ratio of their side lengths is

\[\frac{Vt}{ut} = \frac{V}{u},\]and if we then consider the small triangle, equating the previous ratio to the ratio of the same two side lengths, then

\[\frac{V}{u} = \frac{w'}{w} \implies w'= w\frac{V}{u}.\]Therefore, the total area of the orange parallelogram is

\[w' \times L = w\frac{V}{u}L.\]The total combined area of the orange and yellow parallelograms is then

\[hL + w \frac{V}{u}L.\]If we take this area, and multiply it by the number of raindrops per unit area $n$, then we get the total number of raindrops $N$ that hit you:

\[N = nhL + nwL\frac{V}{u} = nL \left( h + \frac{V}{u}w \right)\]which corresponds directly to how wet you get! Notice that $N$ is inversely proportional to $u$; what’s more, we see that no matter how fast you run, no matter how large you make $u$, $N$ can never be less than a constant value, $nhL$, the amount of rain that hits your front.

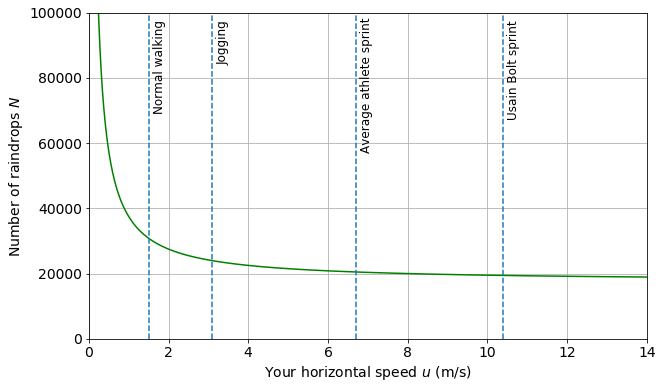

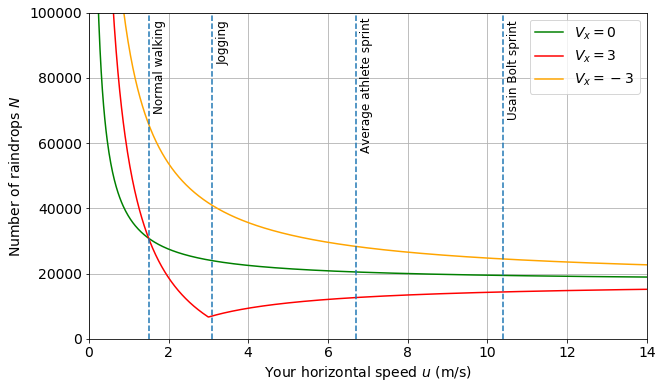

Let’s take some ballpark numbers: $n = 100~/m^2$, $L = 100~ m$, $h=1.75~m$, $w=0.25~m$, and $V=8~m/s$. A plot of $N$ against $u$ looks something like this:

I’ve also added some different running speeds of interest indicated in dashed lines, with information from this seemingly legit site. Anyhow, the values seem pretty reasonable.

The shape of the graph makes sense. As expected, $N$ is inversely proportional to $u$, and we see that as $u$ gets larger and larger, $N$ never dips below a certain value $nhL$, or in this case $100\times 1.75 \times 100 = 17500$.

According our little model here, if you jog instead of walk, you’ll get around 22% less wet. Not too bad!

However, if you sprint at an average athlete’s pace, you’ll only get 14% less wet than if you jog. And if you pull off a Usain Bolt world record sprint, you’ll only get 5% less wet than if you did a normal athlete’s sprint.

These percentages will change based on $h$, $w$, or $V$, but for the most part they should be decent approximations.

The takeaway is, the slower you are going, the more it pays off to move faster. If you’re already running at a good pace, you’ll only be a little bit drier for a significant increase in speed. Ultimately, you can even run at the speed of light, but you’ll never be drier than the minimum, $nhL$.

Windy Rain

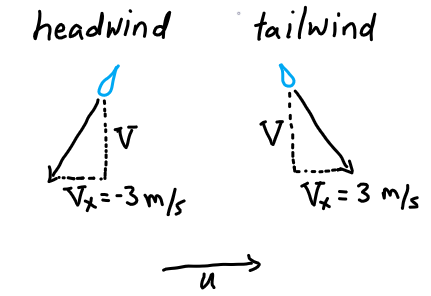

So far, we’ve ignored a complication: the rain velocity can have a horizontal component too. We’ve assumed that the rain falls perfectly vertically, but we know that rain will often fall slanted, caused by a headwind or tailwind.

How can we take this into account?

We can still draw those diagrams with clever triangles like we did before, but it gets complicated quickly. A better way might be to start with the formula we know,

\[N = nhL + nwL\frac{V}{u}.\]This time, we can interpret each term in the equation as a product: the rate at which raindrops hit you multiplied by the time you’re in the rain gives the total number of raindrops that hit you.

Take the second term as an example. What if we rewrote it as

\[nwL\frac{V}{u} = (nwV)\left( \frac{L}{u} \right) ?\]Then, $nwV$ is the rate at which raindrops hit you on top: this makes sense, because this rate is proportional to the density of raindrops, your width, and the speed at which rain falls vertically. An increase in any one of these three quantities will obviously yield a proportional increase in the rate of raindrops hitting you. Naturally, $L/u$, the total horizontal distance divided by your horizontal speed, gives the time in the rain.

Now, the first term: let’s rewrite it as

\[nhL = (nhu) \left( \frac{L}{u} \right).\]This now gives the rate of rain hitting you on the side, from the same reasoning as before. The only difference is, we use $u$ instead of $V$ to find the rate of raindrops hitting you, because the speed at which rain comes at you horizontally is now $u$, the speed you move…if the rain were falling straight down.

If it’s a windy day, and the rain itself had a horizontal component $V_x$, then the relative speed at which rain comes at you horizontally is not just $u$, it’s $u-V_x$. We don’t care if it’s negative or positive, since rain can wet you from both front and back, so let’s put it in absolute value. The first term in our equation becomes

\[(nh)|u-V_x| \left( \frac{L}{u} \right)\]and our modified equation for $N$ becomes

\[N = nhL \frac{|u-V_x|}{u} + nwL\frac{V}{u}.\]Let’s take two cases

with two different values of $V_x$, and see what their plots look like, assuming the same parameters as before:

With a headwind, it’s even more beneficial to move faster. However, you’ll always be wetter than with no wind, no matter what speed you run.

With a tailwind, things get interesting. If you run at $u=V_x$, then the first term in our equation is zero - producing that sharp minimum you see on the red graph. Funnily enough, after that point, the faster you move, the $wetter$ you get!

In all cases, as you run faster and faster, the number of raindrops you hit will approach the same value - $nhL$.

Takeaways

We have two neat conclusions:

- If there’s no wind or a headwind, the faster you run, the drier you’ll be! However, if you’re initially slow, then you’ll see a big difference in adding speed. If you’re initially already fast, you’ll see only a small difference in adding the same speed.

- If there’s a tailwind, then there’s an optimal speed where you’ll be driest - match the horizontal speed of the rain!

You might also wonder what would change if we worked in three-dimensions. The equations and graphs would stay fairly similar, and we mostly need to tweak the units a little bit. For example, we only need to change $n$ from being the density of raindrops per unit area to density of raindrops per unit volume, defining the unit volume using the depth/third dimension of the person. If rain comes from the side with a crosswind, then we’d need to add a separate term to account for that. It could affect the shape of our plots.

Our approach is admittedly crude and simple, with plenty of dubious assumptions. There are so many holes someone can poke in our simple answer. What about moving legs - the fact that someone’s legs move at different speeds at different points in their stride when running? Or how about the extra splashing water they fling up when running faster? Or how there might be a certain saturation point where someone can’t get any more soaked? All of these problems, and more, could be causes of deviations from our model.

You can go as deep as you like down this rabbit hole of a problem. We’ve used a rather crude rectangle as an approximation for a person, but apparently using an ellipsoid yields somewhat similar but subtly distinct conclusions [1]. Want more? The most modern and comprehensive treatment of the problem is probably by Franco Bocci, in 2012 [2].

Or, you know, just be prepared with a rain jacket, so you don’t have to worry about any of this…

References & Further Reading

- Hailman & Torrents. Keeping Dry: The Mathematics of Running in the Rain. Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 82, Issue 4. 2009.

- F. Bocci. Whether or not to run in the rain. European Journal of Physics, Vol. 33. 2012.

Have a suggestion or found an error? I'd be happy to know at alex.wen[at]alumni.ubc.ca.